Learn More About the IJC’s Responsibility to Assess Canada and the United States’ Progress Under the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement

Communities of people, plants and animals rely on clean, healthy Great Lakes water quality. Nearly thirty percent of the combined Canadian and US population live, work and play in the region.

Recognizing the importance of the Great Lakes, the federal governments of Canada and the United States signed the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement in 1972, updated most recently in 2012.

The Agreement commits the two governments to work together to protect, enhance and restore the water quality of the Great Lakes and St. Lawence River (to the international boundary).

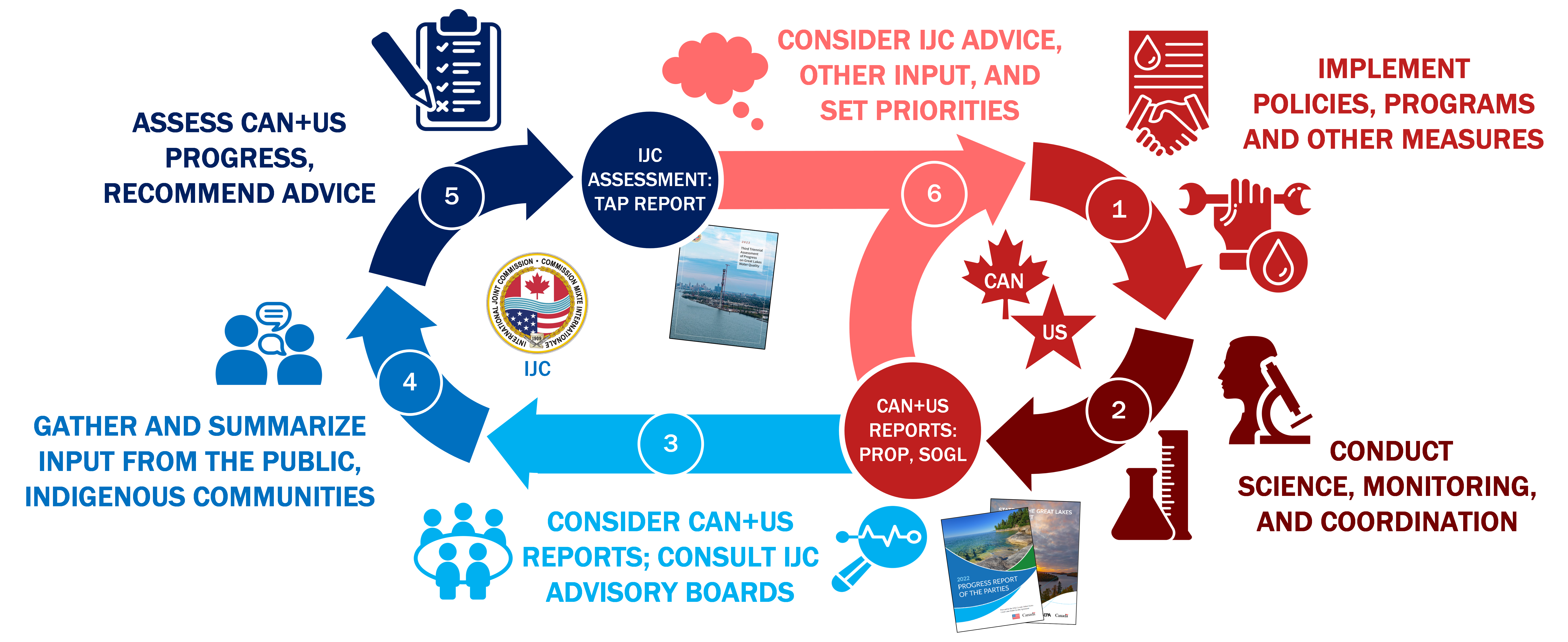

The International Joint Commission (IJC) helps prevent and resolve disputes and provides science-based advice on matters affecting waterways shared by Canada and the United States. (Learn more about the IJC in this video). In the Great Lakes, the IJC has responsibilities under the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement to conduct research, engage with the public, assess governments’ progress, and recommend advice to the Canadian and US governments.

The Agreement aims to help ensure the waters of the Great Lakes are healthy and safe. The Agreement establishes nine general objectives for Great Lakes water quality. These include shared goals for the lakes to be a safe source of drinking water, allow for unrestricted swimming and enjoyment, and allow for the healthy consumption of fish and wildlife.

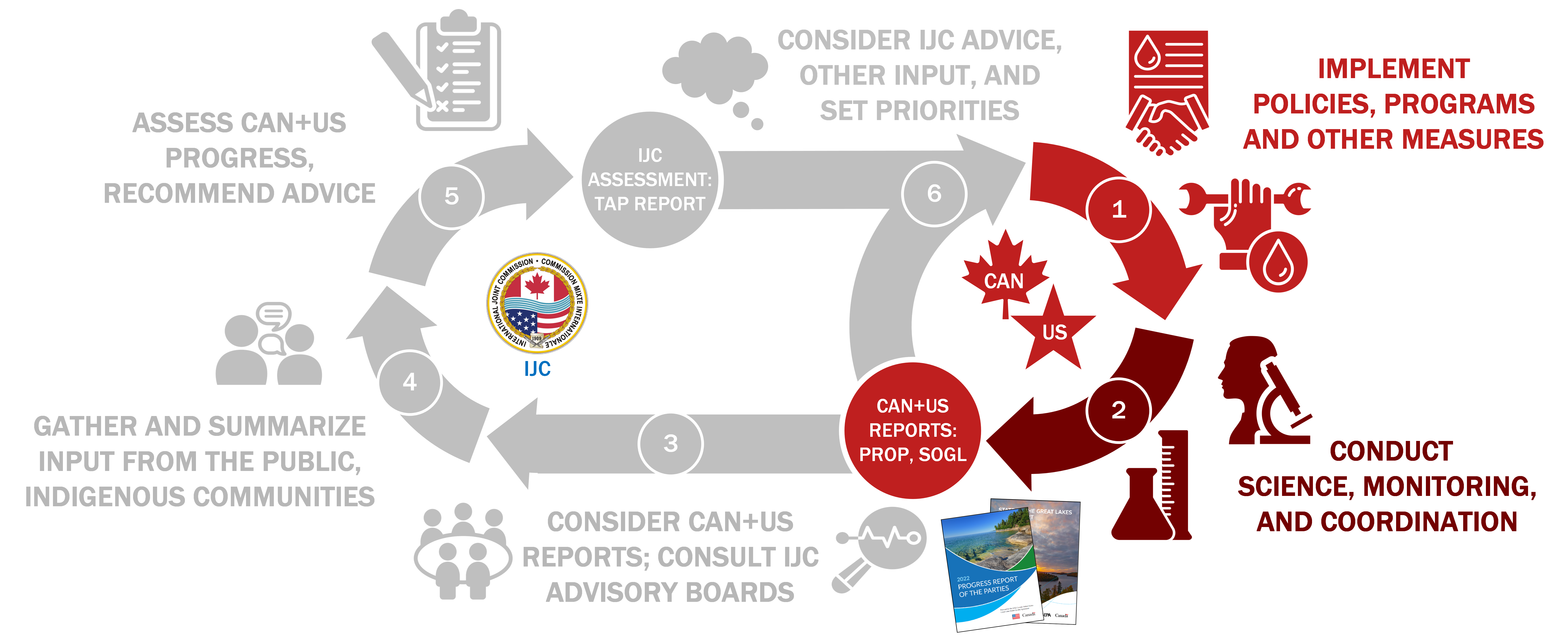

Canada and the United States implement policies and programs to address the Agreement’s objectives. Programs—like cleaning up toxic hotspots known as “Areas of Concern”— implement and coordinate activities that address issues like pollution, invasive species, and habitat restoration. These activities are what move the needle to improve Great Lakes water quality.

Monitoring and science are also essential. Through the Cooperative Science and Monitoring Initiative, Canadian and US governments work together to sample each Great Lake on a five-year cycle. Regular water quality monitoring helps explain the impact that programs and activities have on the ecosystem and can inform future actions and priorities.

The federal governments do not implement programs and conduct monitoring alone. Provincial and state agencies, municipal and regional governments and First Nations, Métis and Tribal governments and agencies also conduct programs that help advance the Agreement’s goals (Figure 1).

Every three years, the governments create two self-report cards: the Progress Report of the Parties and the State of the Great Lakes. The Progress Report of the Parties summarizes the programs, policies and activities the governments accomplished in the last three years. The State of the Great Lakes Report documents on the health of each lake through the status and trends of a set of ecological indicators.

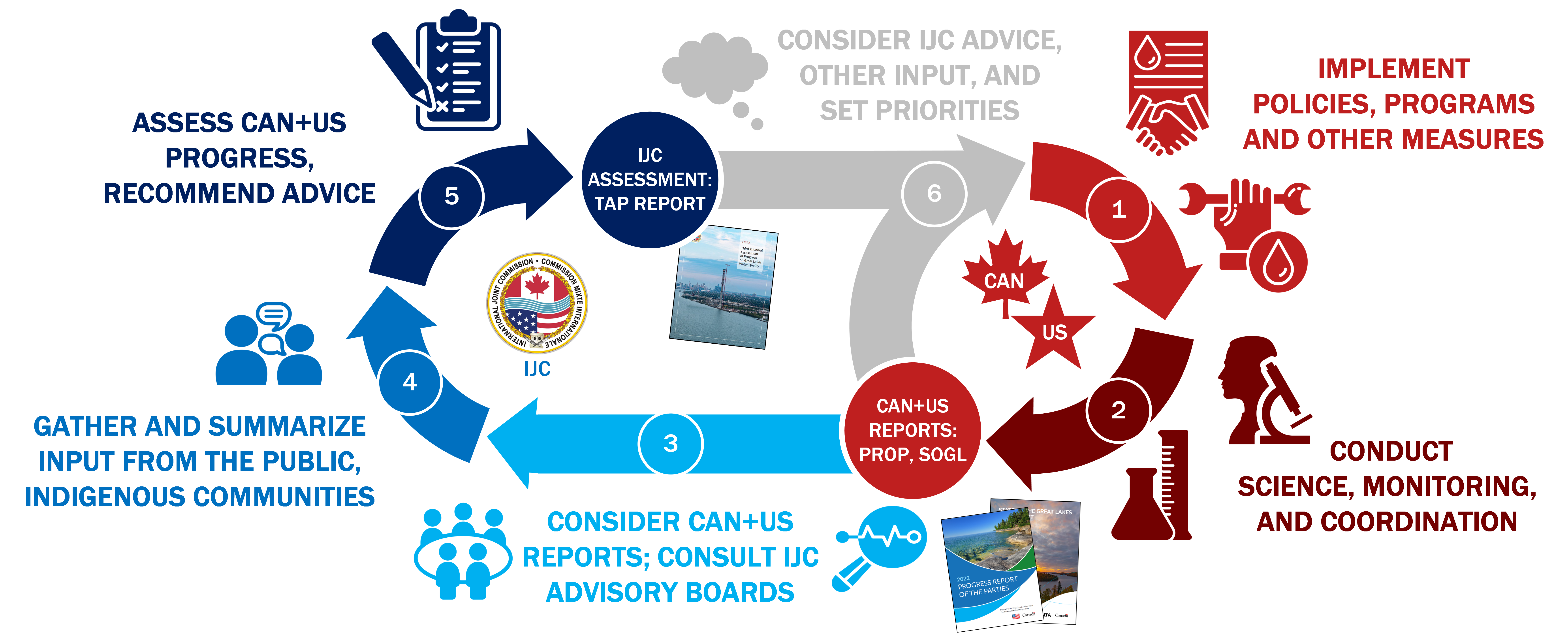

Following the reports published by Canada and the United States, the IJC begins its independent evaluation of progress called the Triennial Assessment of Progress. As part of its review, the IJC considers the governments’ two self-report cards and consults with its Great Lakes Water Quality Board, Great Lakes Science Advisory Board, and Health Professionals Advisory Board, considering the boards’ relevant studies and advice to the Commission.

Input from the public and First Nations, Métis and tribal communities is another crucial aspect of the IJC’s assessment. The people that live around the Great Lakes are closely intertwined with the health of the lakes. They experience the problems the lakes face firsthand and are on the Commission’s eyes and ears, witnessing the front lines of restoration and protection of the lakes. Additionally, Indigenous peoples are the original caretakers of the waters, with thousands of years of knowledge, experience, and wisdom about the lakes’ ecosystems. Indigenous communities hold unique perspectives on and relationships to the Great Lakes and are vital to understanding what must be done for the lakes in the future. The IJC listens to feedback from the public and Indigenous communities, synthesizes comments, and uses that input to help inform recommendations to the Canadian and US governments.

The IJC brings together all this information to assess the governments’ progress towards achieving the objectives of the Agreement. This assessment is detailed in the IJC’s Triennial Assessment of Progress Report which provides the governments of Canada and the United States with recommendations (Figure 2).

The Canadian and US governments may consider this advice from the IJC, as well as other advice to adjust and implement their programs and policies for the next three-year period, completing the Great Lakes water quality assessment cycle.